Beethoven: Artist and Hero

Harry Costin

As we seek to understand how Beethoven explored the theme of the hero in his music, we immediately discover that, led by his unique star, the composer himself was transmuted into a hero. His own difficult life was a true Forge of Vulcan out of which emerged an extraordinary Universal Man.

Even more so, we not only discover the extent to which the life of the genius was heroic due to the dire obstacles he had to overcome, but also that through his own transmutation expressed in his music, the artist-hero leads us in a similar way through an ascending path he himself had to follow. This process brings about a true catharsis and a profound transformation in ourselves.

It is thereby that even in the most humble way whether as listeners, or interpreter-apprentices, those who approach his music feel how in a mysterious way it penetrates through the pores of the soul, becoming a rich vocabulary that can express the most diverse human feelings. The soul, armoured by the new language, enters into a dialogue with the music of the genius, and the most varied forms and melodies create a new symphony inside of us. New compositions full of meaning are born in whoever discovers inside of themselves these “beautiful divine sparks” as Beethoven himself said at the end of his life, a time when he was already deaf to the world but full of the music born in heaven and descended upon earth.

Thus, the music of Beethoven, born out of the transmutation of infinite human experiences becomes our own music. The titan is no longer a far away and solitary genius, since in a mysterious way, our destinies become intertwined. He, Beethoven, I, the little philosopher-musician led by the genius, and We, all of humanity, fuse together into a harmonious accord.

Reflecting upon the alchemical power of the music of Beethoven, we cannot but remember Wagner, who tells us in his autobiography that one night he heard a symphony of Beethoven and became gravely sick. When he recovered, he had been reborn as a musician.

The divine music of the hero, which has become our own, exists in our inner space, and we feel immersed in a forest of gigantic columns as pilgrims of the hypostyle hall of the temple of Karnak, or silent spectators in a forest of centenary sequoias. The columns that surround us are made of sound; they build a gigantic bridge which unites heaven and earth. It is the second movement of the Seventh Symphony full of hopes and mysteries…

Let us start our journey…

The forge of a Hero

It is worth remembering that for the ancient Greeks, a hero was a son of god or goddess and a human being who became prominent for his Virtue, Beauty, Purity, etc. A hero was a living symbol of the human potential. He was crucified between Heaven and Earth and his path of celestial ascension entailed great difficulties and sacrifices, as we can see in the myths about the labours of Hercules or Theseus.

When referring to musical geniuses, there is probably no other composer to whom the concept and epithet of hero has been more frequently applied than Beethoven. The theme of a hero inspired several of his masterworks, such as the Third Symphony, the Eroica, and the Funeral March of the Sonata with Variations No. 12.

But Beethoven's true hero, as most of his biographers acknowledge, is the composer himself. How was it possible for a child, whose alcoholic father forced him to study music in the middle of the night, often punishing him in the most cruel way, not to end up hating music? How can we fathom that, deprived of the most important of his instruments, his hearing, from the zenith of his life, Beethoven was still able to raise a hymn to joy in his Ninth Symphony? He completed the Ninth barely three years before his departure from this world. The lyrics of the choral part express the composer’s dream in the words of Schiller: 'all Men become Brothers'. Finally, Beethoven was confronted with a third brutal test, when he was already virtually disconnected from the world by his galloping deafness. He attempted to pour into his nephew all his infinite power of human love, and also his experience as a musical virtuoso, but was rejected by his brother’s son in the cruellest way.

In the case of Beethoven, the search for the heroic in his life and work is by necessity multifaceted. We suggest, that strictly speaking there are three main keys to understanding the hero and what is heroic in Beethoven:

- The interpretation of the theme of the hero in his music;

- The heroic life of the composer, who had to sacrifice his career of a performer due to his deafness; and

- Beethoven's Ideal of Universality, since the hero sacrifices his own life on the altar of humanity.

A fourth possible key of interpretation is the ideal of the spiritual ascent of the individual human being. This allows us to better understand how the theme of the hero permeates all of Beethoven's work.

Challenges of destiny

Our aim is not to delve into the complex psychological and at the same time simple factual biography of Beethoven, but to highlight some aspects of his development. We want to follow his path through life as if life itself were the Forge of Vulcan in which the weapons of the Gods are formed. In his case, an unrivalled human instrument, one through which Apollo and the Muses expressed themselves, was forged.

Beethoven was born into a family of musicians. He greatly admired his grandfather who was a chapelmaster at the Bonn court, and a role model for the composer. His father, also a musician, was weak in character and did not resemble in any way the imposing grandfather figure. Unfortunately, like his own mother, both Beethoven's paternal grandmother and his own father succumbed to alcoholism, a weakness that Beethoven himself would fight against with determination and success.

Another biographical fact is worth mentioning. Because of his father’s alcoholism, Beethoven was forced to assume the financial responsibility for his family since he was almost a child. He began working as an assistant court organist being only thirteen. Therefore, later in his life self-control became fundamental for the musician, as well as a morality self-imposed by his will that also dominated over his volcanic character.

As for the impetuous character of the genius, more than once young Beethoven was referred to as a 'demon.' He seemed to embody the image of Plato's Phaedrus , a celestial charioteer driving a chariot drawn by two horses: one of them fiery and uncontrollable, and the other docile and obedient. In Beethoven the greatest virtues and generosity coexisted with extreme pride and contempt for vulgarity.

But it was life itself that tested Beethoven's spirit. Despite a tough childhood, the musician's genius prevailed in a difficult environment. He became a master performer and improviser, and this opened the doors of Vienna for him. Thus, in 1800 at the age of 30, Beethoven was recognized and admired in Vienna, a city affected in those years by the powerful waves of the French revolution and the coming Napoleonic invasion.

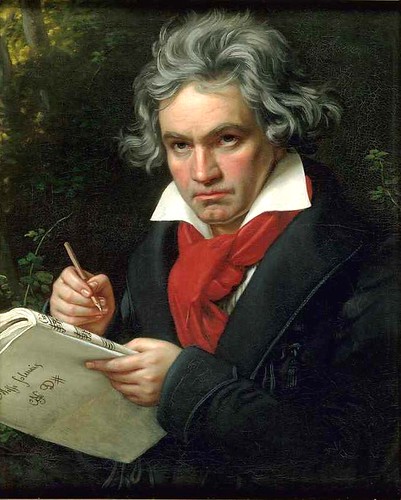

Romain Rolland gave us a masterly description of the genius of that epoch in his writing 'Portrait of Beethoven at 30 years of age”:

“The man I am studying … is the Ego of the period of combat. … He is the masculine sculptor who dominates his matter and bends it to his hand; the master-builder, with Nature for his yard.”

Beethoven in his thirties was a man of great strength and vigour, with a powerful musculature and an athletic body with a skull that stood towering above others like “the dome of a temple” and who roared “with the voice of a lion”. The genius had an innate sense of rebellion that led him to write to a nobleman: “Prince, what you are, you are by an accident of birth, what I am, I am by myself.”

External difficulties were reflected in the composer’s inner mirror. Beethoven’s music was a fruit of a supreme effort of concentration. He captured an idea, a “heavenly spark” and translated it into sound. In the words of Romain Rolland:

“Once Beethoven takes hold upon an idea, he never lets it go until he possesses it wholly. Nothing can distract him from the pursuit. It is not for nothing that his piano playing is characterised by its legato…”

This contrasted with the style of Mozart, one of Beethoven’s early influences, which was characterized by its delicacy and clarity.

We believe that a musical work composed some five years earlier, the first of his piano sonatas Op. 2, No. 1 published in 1796, provides a magnificent portrait of the young genius, already established in Vienna.

The 32 sonatas by Beethoven are deeply autobiographical, and this first one already provides a complete picture of what was essential for Beethoven. The first movement in F minor, the same key as his Appassionata, one of his best-known sonatas of maturity, is very agitated and full of pathos. The pain felt by the composer is transmuted into energy and movement. The Adagio of the second movement plunges us into an ocean of inner fulfilment. Pain is transformed into energy and energy gradually leads to peace. The final movement, after a peaceful minuet, is energy released from pain and transformed.

The hero in the music of Beethoven

The theme of the hero appears in an explicit mode in the Sonata No. 12, op. 26 in A flat major and in the Symphony No. 3, the Eroica, op. 55 in E flat major. Both works represent a turning point towards the so-called second period of maturity of the composer, in which Beethoven changed classical forms in an important manner.

The Sonata No. 12 composed between 1800 and 1801 begins with an unusual andante with variations theme in A flat major. To introduce variations into the movement of a sonata deviates from the classical model, and reminds us of the fact that Beethoven was the undisputed master of improvisation and, therefore, of variations.

The Sonata includes the third slow movement entitled by the composer “Funeral march on the death of a hero”. In the same way as in the slow movement of the Eroica symphony, the mood of the funeral march is solemn. A great man has died, and he is remembered by all. We imagine a cold day of autumn with only meagre sunlight.

The funeral march is preceded by scherzo allegro molto. Irony preceding a funeral solemnity? Although the word “scherzo” implies a play, a joke, we are inclined towards a classic interpretation in the sense of drama. This means that a human life is a drama, a play of light and shadows.

Beethoven’s inner world is shaped by a unique emotional framework and contrasting moods, but a vital force arrives in a triumphant manner. It is notable that this extraordinary funeral march is preceded and followed by allegro movements, both full of energy.

The sonata might also have influenced Chopin, who composed his own funeral march, integrated into his second piano sonata. It is said that the No. 12 was the only Beethoven sonata Chopin interpreted in public.

In his funeral march Beethoven leaves aside any complexity, and the piano appears to imitate winds and drums, while the tonality searches other horizons starting with the base A flat minor.

The Third Symphony

The Third Symphony is Beethoven's best-known work in which he describes the hero through music. Originally dedicated to Napoleon, the dedication was later dropped and the symphony became a tribute to the fallen hero and to his memory in a generic sense. Like in the sonata No. 12, we attend the funeral of a great Man, and the feeling of greatness expressed through music seems simple, but is more powerful than the feeling of sadness.

The first original page of the Eroica Symphony

Beethoven began to compose his opus magnum during his stay in Heiligenstadt in 1802, and ended it during the spring of 1803 and May of 1804. At that time, he also wrote the so-called Heiligenstadt Testament, which is actually a dramatic letter addressed to his brothers, which was never sent. In the letter, the composer described his painful and forced exile from the world, and planned his own death. When reading the letter and listening to the Eroica, we are astonished by how the personal drama experienced by the genius, because of his growing deafness, was sublimated though music that tells the myth and tragedy of the death of a hero. In the music, the individual drama is dissolved into the universal human experience. An individual hero sacrifices himself so that “humanity” in a spiritual sense can be born.

This symphony, which deals with the theme of the hero in a strict sense, represents the beginning of a new period in Beethoven’s life. Among the innovations is its length. It lasts twice as long as usual symphonies of that period, which means about 45 minutes. Originally it was dedicated to Napoleon and was entitled “Bonaparte”. The legend says that Beethoven changed that dedication when he found out that Napoleon crowned himself an emperor. Nevertheless, the new title of the Sinfonia eroica composta per festeggiare il sovvenire d’un gran uomo shows that a change of the dedication did not change the essence of the music.

The first movement allegro con brio in E flat major begins with an emphatic chord that highlights the basic key. This chord is repeated, and in the third repetition we end up with the solitary E flat, and the chord of the first melody is dissolved into: E flat, G, E flat, B flat, E flat, G, B flat. Can we find in this simplicity the mystery of the trinity, the three in one? Let us remember the three repeated chords using the same E flat tonality at the beginning of Mozart’s Magic Flute.

The second movement is the famous Funeral March in C minor, a key it shares with the Fifth Symphony, and which was full of meaning for Beethoven. The genius considered that each key embraced a whole world in itself, a quality lost if the music was transposed to another tonality. The double basses have their own melodic identity, which does not duplicate the one of the cellos, and paint the atmosphere that frames the march. We have the intervention of a trumpet in the middle section. In the reprise we find a fugue, which is not a simple return, but an expression of heightened pain.

The third movement is again in E flat major, it is a scherzo, allegro vivace. Let us remember that in the Sonata No. 12 the scherzo precedes the funeral march. We are surprised again by the composer who uses the contrast between a slow movement and the other ones in which we have a predominance of agitation and a full development of energy.

The finale, allegro molto, interprets through the orchestra the idea of the variations Op. 35. It is curious that in the Sonata No.12 the variations constitute the first movement. Are we in front of a mirror structure that is not mentioned by the analysts? This might be an idea worth investigating.

The Fifth Piano Concerto

This concerto in E flat major Op.73, known as the Emperor concerto, is the last piano concerto by the composer. It was written between 1809 and 1811 in Vienna and is dedicated to Rudolf Archduke of Austria, patron and disciple of Beethoven. It was a time of rich creativity for Beethoven, in spite of the world being shut out from his ears because of his increasing deafness. During this period he also composed the Fourth Piano Concerto, which will be described below, and the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies.

The allegro assumes the form of a sonata with its three themes: the first two are introduced by the orchestra, and the third one by the piano. Some innovations, among them several cadenzas, announce musical formulas, which would later be used in romantic works, such as the Piano Concerto of Mendelssohn or the First Piano Concerto of Tchaikovsky.

This first movement surprises us with its spaciousness, like an open and vast horizon. It is a lofty world which only a spiritual being soaring high up can conceive and embrace. Starting from this luminous horizon, we begin to build a wide staircase that appears to be made of transparent marble and constitutes a true ladder leading to the heights.

The second movement is of an extremely lyrical nature. The theme, which will be repeated three times with variations, is introduced by the orchestra. The coda ends by presenting to us slowly the main theme of the third movement.

Jacob's Dream (Jacob's Ladder) by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

The powerful image, involuntarily suggested to us by this music in the most intimate manner, is the one of the spiritual being we encountered earlier, whose heart is full of compassion and who extends his hands full of love and hope towards humanity from his celestial heights. It reminds us of those medieval representations of Jacob’s Ladder, a ladder leading towards heaven on which beings that have ascended to the heights are extending their hand to help those who are striving to climb upwards.

The third Allegro movement shows us a composer full of vigour and enthusiasm. This movement is a song to life itself, as well as a magnificent closure to Beethoven´s five piano concertos. In all of these piano concertos we discover true treasures, hidden in a continuous dialogue between the orchestra and the soloist. We will later analyse the second movement of the Fourth Piano Concerto.

Beethoven at 40 years of age

Who is the man who composed these works of maturity? At this time the genius had already lost most of his hearing, moving further away from the world with great sorrow, as he himself expressed it. From this period, we have an important testimony about the artist by Bettina von Armin, née Brentano. This is one of the most complete descriptions of the genius at the time when he confronted the greatest test of his life. We reproduce it in full.

[Bettina von Arnim to Anton Bihler]. July 9, 1810.

I did not make Beethoven’s acquaintance until the last days of my stay there. I very nearly did not see him at all, for no one wished to take me to meet him, not even those who called themselves his best friends, for fear of his melancholia, which so completely obsesses him that he takes no interest in anything and treats his friends with rudeness rather than civility. A Fantasy he had written, which I heard played in admirable fashion, moved my heart, and from that moment on I felt such a longing that I tried by all means to meet him. No one knew where he lived, since often he keeps himself altogether secluded. His dwelling-place is quite remarkable: in the front room there are from two to three pianos, all legless, lying on the floor; trunks containing his belongings; a three-legged chair; in the second room is his bed which—winter and summer—consists of a straw mattress and a thin cover, a wash basin on a pinewood table, his nightclothes lying on the floor. Here we waited a good half-hour, for he was shaving at the moment. At last he came in. In person he was small (for all his soul and heart were so big), brown, and full of pockmarks. He is what one terms repulsive, yet has a divine brow, rounded with such noble harmony that one is tempted to look on it as a magnificent work of art. He had black hair, very long, which he tosses back, and does not know his own age, but thinks he is fifty-three.

I had been told a great deal about how careful one has to be in order not to rouse his ill will; but I had formed quite another estimate of his noble character and had not been mistaken. Within fifteen minutes he felt so kindly toward me that he would not let me go, but kept walking up and down beside me and even accompanied me home and spent the whole day with us, to the great astonishment of his friends. This man takes a veritable pride in the fact that he will neither oblige the Emperor nor the Archdukes, who give him a pension, by playing for them, and in all Vienna it is the rarest thing in the world to hear him. Upon my asking him to play he replied: “Well, why should I play?”

“Because I would like to fill my life with all that is most wonderful, and because your playing will be an epoch in my life,” I said.

He assured me that he would try to deserve this praise, seated himself beside the piano, on the edge of a chair, and played softly with one hand, as though trying to overcome his reluctance to let any one hear him. Suddenly his surroundings were completely forgotten, and his soul expanded in a universal sea of harmony. I have become excessively fond of this man. In all that relates to his art he is so dominating and truthful that no other artist can pretend to approach him; with regard to the rest of his life so naïve, however, that one can do with him what one will. His absent-mindedness in this last connection has made him a veritable object of ridicule; and he is taken advantage of to such an extent that he seldom has enough money to provide the commonest necessities. His friends and brothers use him; his clothing is torn, he looks quite out at the elbows (something which Nussbaumer should note), and yet his appearance is noble and imposing. In addition he is quite hard of hearing and can hardly see. But when he has just composed something he is altogether deaf, and his eyes are confused as they turn toward the outer world: this is because the whole harmony moves on in his brain and his thoughts can busy themselves with nothing else. Hence he is cut off from all that keeps him in touch with the outer world (vision and hearing), so that he lives in the most profound solitude. When one speaks with him at length for a time and stops for his reply, he will suddenly burst forth into tone, draw out his music-paper and write. He does not follow conductor Winter’s method, who sets down what first occurs to him; but first makes a great plan and arranges his music in a certain form in accordance with which he works.

During these last days I spent in Vienna he came to see me every evening, gave me songs by Goethe which he had set, and begged me to write him at least once a month, since he had no other friend save myself. Why am I writing you all this in such detail? Because, first of all, I believe that like myself you can understand and esteem such a character; secondly, because I know what injustice is done to him, merely because people are too petty to comprehend him. And so I cannot forbear drawing his picture just as I see him. In addition to all else, he takes care of all who confide in him with regard to music with the greatest kindness: the veriest beginner may put himself into his hands with all confidence. He never grows weary of advising and helping him, this man who simply cannot bring himself to clip off a single hour of his free time.

The man and the path of the hero

Although it is evident that the hero of Beethoven is almost a quasi-divine being due to his wideness of sight, and that appears in his works in an explicit manner only several times, we believe that in a broad sense the heroic theme is not only a leitmotiv of his own life, but also permeates all his work. The examples are many, but let us choose as an incomplete illustration the Fourth Piano Concerto No.4, Op. 58 and the Seventh Symphony.

The Myth about Orpheus and the Fourth Piano Concerto, Op. 58.

The American musicologist Owen Jander offered a courageous hypotesis, that develops in an important manner a comment by Adolf Bernhard Marx, a well-known Beethoven biographer of the 19 th century. The hypothesis is that the second movement of the Fourth Piano Concerto Andante con Moto reflects musically the story of the descent of Orpheus to Hades in search of his beloved Eurydice, as narrated by Ovid in his Metamorphoses.

In his 10 th book of the Metamorphoses, Ovid describes the sad episode of the death of Eurydice and the failed attempt of Orpheus to return her to the world of the living because of his own imprudence.

On the day after the sacred marriage, blessed by the presence of Hymen, the bride died when she stepped inadvertently on a snake hidden by the vegetation of a meadow. The poet, accompanied by his lyre, mourned deeply the loss of his beloved and implored the rulers of the underworld, Hades and Persephone, to release the one who had departed prematurely if the great god Amor was powerful in those regions…

The gods listen to the mournful supplication; the shadows and even the immutable Furies are moved by the irresistible magical song of Orpheus. The great Lord of the Depth and his Queen grant the poet the unheard-of: Eurydice is allowed to return to the world of the living, but on condition that as she moves towards the light, the poet must not turn his head to see her…

“But Orpheus was frightened his love was falling behind; he was desperate to see her. He turned, and at once she sank back into the dark. She stretched out her arms to him, struggled to feel his hands on her own, but all she was able to catch, poor soul, was the yielding air. And now, as she died for the second time, she never complained that her husband had failed her – what could she complain of, except that he’d loved her?”

The Fourth Piano Concerto of Beethoven Op. 58 in G major.

An aura of mystery surrounds this concerto composed in 1805-1806 during an immensely creative period for Beethoven. It was the time when he wrote other famous works such as the opera Fidelio, the Waldstein and the Appassionata piano sonatas, the Triple Concerto, the Razumovsky string quartets, and tge Violin Concerto. The dramatic moments described in the Heiligenstadt Testament appeared to be far behind the composer.

Beethoven was 35 years old, the same age when Mozart passed away. And he also began to die for the world as his deafness progressed. This forced internalization was somehow tragically related to the Fourth Piano Concerto. The premiere of this concerto with Beethoven himself at the piano on 22 December 1808, was the last time the genius performed in front of the public as an instrumental soloist. During that premiere, which lasted for about four hours, the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies were played for the first time, as well as the movements of the Mass in C major and the famous Choral Fantasy, composed speedily to serve as a glorious finale for the concerto.

The Fourth Piano Concerto is a wonderful dialogue between the piano and the orchestra. The first movement surprises us not only because the piano begins the action, but also since it contrasts with the grandiose beginning of the Fifth Piano Concerto, the Emperor. In the first movement of the Fourth Piano Concerto, the piano begins timidly with a rhythmic motive similar to the Fifth Symphony, which emerges mysteriously as if continuing an interrupted dialogue. However, it is not the first movement that we want to focus on, but the second one – the Andante con Moto.

Andante con Moto

The brief second movement, in which we find a strict segregation between the soloist and the string orchestra (the rest of the orchestra is in silence) is so astonishingly beautiful that it captured the imagination of the Romantics such as Chopin and Schumann, and deserves a separate analysis.

The interpretation which relates this movement with the myth of Orpheus is owed to Adolf Bernhard Marx, the famous 19 th century biographer of Beethoven. He referred to the intense poetic quality of the work in the following terms:

“This is one of the most beautiful concerts worthy of appreciation. It is also a poetic work that has no parallel in the series of concerts. It is a concert that has been composed by a musical poet and only merits being interpreted by a musical poet. Already the first movement reflects the delicate anxiety of a soul full of almost childish joy, but capable of the most intensive passion.”

And according to the analysis of the biographer, in the second movement of the Andante con Motto we encounter the spirit of the poet in a more defined manner. We are now in the centre of a dramatic scene which confronts the piano with the string orchestra (the other instruments keep silent,,). The piano, with its intensive poetic (legato) melody is in sharp contrast with the motive interpreted in octaves by the strings (forte and staccato). Could this be a similar dialogue to the one between Orpheus and the Furies when the hero attempted to enter Hades as represented by Gluck in his opera Orpheus and Eurydice? The scene to which Adolf Marx referred to is the following:

Gluck: Orfeo ed Euridice, Act Two, Scene One: Furies

CHORUS

Who is this

who draws near to us

through the gloom of Erebus

in the footsteps of Hercules

and of Pirithous?

May the savage Eumenides

overwhelm him with horror,

and the howls of Cerberus

terrify him

if he is not a god.

ORPHEUS

Oh be merciful to me, ye Furies, ye spectres, ye angry shades!

CHORUS

No! — No! — No!

ORPHEUS

May my cruel grief at least earn your pity!

CHORUS

Wretched youth,

what seek you? What is your purpose?

Here dwell naught

but grief and lamenting

in these fearful,

mournful regions!

ORPHEUS

A thousand pangs I too suffer,

like you, o troubled shades;

my hell lies within me,

in the depths of my heart.

CHORUS

Ah! What unknown

feeling of pity

sweetly comes

to soften

our implacable rage?

The interpretation of Owen Jander

Based on Adolf Marx, the North American musicologist Owen Jander has explored the historical and musical circumstances of a possible relationship between the Fourth Piano Concerto and the Myth of Orpheus. Jander found a reference to the work by Czerny, the famous pianist and disciple of Beethoven, which may hint at the possible programmatic nature of the movement Andante con Motto:

“In this movement (which in the same way that the entire concert belongs to the finest and most poetic creations of Beethoven) we cannot but think about an ancient tragic scene. The interpreter must feel how intense and passionate his solo has to be to reach the necessary constrast with the powerful and austere passages of the orchestra that starts withdrawing gradually.”

What is noticeable in both the original score and the many interpretations of the movement, is the musical dialogue, in which the orchestra at first overwhelms the lyrical theme of the piano with impetuosity, and then ends up being effortlessly subjugated by the piano (the piano does not raise the voice but only emphasises and expands the lyrical motive while the orchestra slowly submits to it).

Musical and literary sources of the Myth of Orpheus

In a daring interpretation Owen Jander suggested a direct and textual relationship between the movement and the myth of Orpheus. According to Jander, the original interpretation by Adolf Marx only tried to establish a parallel with one of the musical sources of the myth of Orpheus - the Orpheus and Erydice by Gluck. Adolf Marx saw not only similarities but also differences between the interpretation of Gluck and the suggested musical dialogue of Beethoven.

By contrast, Owen Jander indicates that the differences may be explained if we take into consideration the different musical sources of the myth of Orpheus. The two most important classical sources of the myth of Orpheus are the Georgics by Virgil (Book 4, lines 453-527) and the Metamorphoses by Ovid (Book X, lines 1-85, Book XI, lines 1-84). As for musical sources, it is worth mentioning not only the Orpheus by Gluck, but also another lesser-known work about the Orpheus myth by a contemporary of Beethoven, the composer Friedrich August Kanne.

What is especially interesting is that the Metamorphoses of Ovid had been published in Vienna for the first time in 1791 (because of the official censorship controlled by the Jesuits). The classic work had been promoted by famous people close to Beethoven, including Franz von Lobkowitz (in whose palace the Fourth Piano Concerto was premiered in private). In other words, Ovid's work, in addition to its importance of presenting the main themes of classical mythology, was fashionable because it had been previously censored. On the other hand, Kanne was a close friend of Beethoven, who therefore knew his work well.

Jander suggests the interpretation of the Andante con Motto movement through five musical sections and five programmatic sections. According to the musicologist

“These five programmatic musical sections are, as I see it, incontrovertible. Less klipp und klar (evident) is the specific detail of these sections. By necessity we enter here into the terrain of speculations.”

The five sections are:

I, bars 1-38. Orpheus confronts the hostile Furies of Hades. Based on Gluck, Kanne and Naumann, with references to Virgil and Ovid. The dialogue is between the orchestra and the piano with ever-shorter musical phrases.

II bars 38-47: The Furies are conquered by the Orphic song. Based on Gluck, with references to Virgil and Ovid. This section represents the decrescendo of the orchestra.

III bars 47-55. Orpheus, playing his lyre, guides Eurydice through the infernal regions. Based on Virgil and Ovid and reflecting the tradition that the lyre of Orpheus possesses protective magic. Piano solo with four pizzicato parts in the strings to emphasise the image of a harp in the arpeggios of the piano.

IV bars 55-64. Orpheus breaks his vow and turns to look at Eurydice. Based directly on Virgil and Ovid. Piano solo.

V bars 64-72. Eurydice falls back into the darkness and is reclaimed by the Furies of the infernal world. Based directly on Virgil and Ovid. The orchestra reappears with sound material that reminds us of the beginning of the movement.

Conclusion: Rondo

We may never know whether Beethoven was inspired in a conscious or unconscious manner by the myth of Orpheus, which like the Magic Flute of Mozart reminds us of the supreme power of music. The great hero-musician Orpheus conquered death with his music, a music to which Beethoven dedicated his life, and in honour of which he remained alive (Heiligenstadt testament).

The Seventh Symphony

The Seventh Symphony is another work that suggests an inner path for the human being. Below you will find the interpretation of our friend G. Avery, musician and architect, who has analysed the hero's pilgrimage in the Symphony:

Analysis of the 7 th Symphony (G.Avery)

This analysis is based on the fundamental themes of the myth of the hero, which can be found in all cultures throughout history.

First movement: Poco sostenuto. The worries of the youth.

The introduction into the 7 th Symphony consists of the series of legato passages (clarinets and oboes) punctuated by harmonious tones that develop into ascending semiquaver passages. We feel the rhythmic pulsation as if the work is being born out of waves of increasing intensity (like the subsequent Wagner’s overture 'The Rhine Gold'). But the dense orchestral texture recedes to reveal the melodic line first presented by a solo oboe, then followed by the first violins. The rhythmic motif returns to assert itself with greater strength only to be interrupted by the idealistic melody played by the flute, like the sun penetrating through the clouds. It is as if the melody seeks to find its own identity stumbling over a new rhythmic figure that becomes the motive for the second part of the first movement: vivace in 6/8, a much more joyous and lively movement.

Now the melody proceeds like a young person through a country landscape. All fear of a threatening storm has been transformed into an enthusiastic sense of adventure. The flute presents the theme followed by an echo of the musical phrase by the strings section. The strings conclude their melodic role and the enthusiasm grows. Here we begin to discover Beethoven as a skillful navigator steering the course of his musical composition.

The theme begins to approach its climax and reaches the crest of the wave without losing any of its vitality. This 'wave action' generates within itself a rhythmic pulsation which is capable of maintaining its dynamics for a much longer period than would be possible through the simple rhythmic pulsation.

Even when the movement of the wave recedes we can immediately recognize its imminent return. We feel how the melodic line gains momentum and strength when Beethoven concentrates the entire range of colours of the orchestra in a stroke of singular purpose. The innocent and happy theme reveals its heroic character through each beat. The pilgrimage of the youth is transmuted into the triumphal march of the adulthood.

Second movement: Allegretto. The initiation into adulthood.

The psychological environment has been marked by the key in minor. The hero has entered the enchanted forest. The melody performed by cellos and violas has a dark and gloomy character. When the violins begin to give vigour to the melodic line, the violas and cellos assume a melodic undercurrent that emphasises even more mysterious mood. Both lines progress together just as the winds infuse relentless breath. The wind changes direction revealing an even more delicate melodic performance through a solo clarinet followed by the flute on a base of arpeggiated triplets. The end of this passage has been marked by a descendant line of staccato in which Beethoven uses the entire orchestra as a single instrument that combines all the elements introduced in the proceeding passages

The next section presents an enriched version of the opening melody, in double time, and interpreted by the woodwinds in their upper registers. The staccato passages of the strings seem to tiptoe through the forest foliage as their counterpart flies overhead. This dialogue develops in interchange of fugues and culminates in an overlay of variations on the original theme.

Finally, we have the return to the tempo interspersed with melodic fragments of various instruments to close the movement.

Third Movement: Presto - Assai Meno Presto. The celebration of Life.

The scherzo in F major, the submediant minor of the main key of the symphony (A major), is considered unusual in that the trio (D major) appears a second time. In this way the accelerated time of the presto sections (in 3/4 but that should be counted as a time) alternate with sections meno presto which are much more lighter and slower to generate the form ABABA. Beethoven contrasts the heavily orchestrated, almost dance-like passages of the presto section with more fluid trio interludes in which the illusion of the suspension of rhythm is accomplished through the melody moving above long sustained and unchanging tones. The melody is a metaphor for the continuous passage of time ... the illusion of change ... but underneath this whirlwind of movement resonates the omnipresent purpose of destiny.

Fourth Movement: Allegro con brío. Recognition of an Inner Being.

Everything that precedes this movement could be considered as a simple preparation of the listener for what follows. Here emerges the unleashed fury of forces that have been deliberately suppressed previously. The strings begin to vibrate intensely and the rest of the orchestra joins in incessant rhythmic pulsing. A double rhythmic form of opposites in the low and high registers emerges as the typically Beethoven signature of the movement. The primary melodic motif is surprisingly simple, which gives it great mellability. Through a procession of transpositions it rises and sinks like a tidal wave of sound. The dynamics seem purposefully exaggerated with little mediation between forte and piano. The staccato notes are strong and decisive and create an ineffable sense of marching toward an unseen but certain destiny. Once again, the sound range of the orchestra is developed through rich melodic threads that weave together the orchestral assemble augmented by the string section which reasserts the melodic line. The transition from the playful passages of the flutes, in contrast to the symphonic storm, could be considered an exquisite expression of musical irony and serve to illustrate the Master's use of passion as a catalyst of transformation. Beethoven demonstrates irrefutable mastery in his ability to originate and sustain the climatic momentum. To arrive at the consummation of the work, the melodic line seems to converge on itself to finally erupt into completely cohesive and coherent musical expression with a singular purpose.

The Hero and Humanity

Thus, we arrive at the fourth key of the heroic theme in Beethoven: the hero and humanity. Through his many tests, the hero identifies more and more with all of humanity, the “us” that gives meaning to all his individual sufferings. This consciousness of service to humanity and of Humanity in the spiritual sense of the word, accompanied Beethoven throughout his entire life.

Humanity and fraternity among all human beings constituted the core theme of one of the greatest compositions of Beethoven, his true spiritual testament, the Ninth Symphony.

The Ninth Symphony

Composed between 1818 and 1824, this one hour-long opus magnum was conducted by Beethoven himself, already deaf, in what was to be his last public appearance. The work was declared part of UNESCO’s World Heritage in 2002, and the main choral theme is the anthem of the European Union.

The first movement begins with bars that hint at the tuning of the instruments of an orchestra which seems to explode in a cascade of light. This idea is repeated and followed by dramatic bars alternating with others of serene and luminous music. Are we at the threshold between night and day, waiting for a dawn full of hope?

The staccato of the second movement introduces a great flow of energy, which appears to emulate the pulsating of life itself.

The third movement is dominated by a lyrical spirit that appears like a prelude to the fourth movement in which a choir is introduced, something unheard of for a symphony. The serenity transmitted by this movement is simply divine. All human sufferings have been transmuted and what yesterday was pain, today is love and compassion.

The fourth movement translates into explicit words, the most profound hopes of a human being on the path to their own inner heaven. Beethoven uses the wonderful words of Schiller, a genius who was also forged in the Forge of Vulcan .

We believe that words would be inadequate to transmit the essence of the great choral ending of Beethoven’s homage to Humanity. Therefore, let us explore what the original words suggest to us:

Translation of the Hymn (Ode) to Joy

Note: The words in bold were added by Ludwig van Beethoven.

O friends, no more of these sounds!

Let us sing more cheerful songs,

More songs full of joy!

Joy!

Joy!

Joy! A spark of fire from heaven,

Daughter from Elysium,

Drunk with fire we dare to enter,

Holy One, inside your shrine.

Your magic power binds together,

What we by custom wrench apart,

All men will emerge as brothers,

Where you rest your gentle wings.

If you've mastered that great challenge:

Giving friendship to a friend,

If you've earned a steadfast woman,

Celebrate your joy with us!

Join if in the whole wide world there's

Just one soul to call your own!

He who's failed must steal away,

shedding tears as he departs.

All creation drinks with pleasure,

Drinks at Mother Nature's breast;

All the just, and all the evil,

Follow down her rosy path.

Kisses she bestowed, and grape wine,

Friendship true, proved e'en in death;

Every worm knows nature's pleasure,

Every cherub meets his God.

Gladly, like the planets flying

True to heaven's mighty plan,

Brothers, run your course now,

Happy as a knight in victory.

Be embraced, all you millions,

Share this kiss with all the world!

Way above the stars, brothers,

There must live a loving father.

Do you kneel down low, you millions?

Do you see your maker, world?

Search for Him above the stars,

Above the stars he must be living.

But was Humanity a late discovery by Beethoven, who, seeing himself cut off from his fellowmen by the ordeal of his deafness, found in Universal Love all that he could not find in the love of his 'distant beloved'?

We do not believe so, because of the message of the words with which we close this search for the hero and the heroic in the life and work of Beethoven. The words belong to an aria of the Cantata for the death of Joseph II. - Aria with chorus 'Da stiegen die Menschen ...' (“The Human Beings Climbed”) - composed by the genius at only 19 years of age, in Bonn.

And Humanity ascended towards the light

The Earth turned happily around the Sun

And the Sun warmed everything

With the rays of Divinity

Bibliography

Boston Symphony Orchestra. Program notes of the concert on 23/4/1990. Season 1989-90.

The Ode to Joy translated by Michael Kay

http://saxonica.com/~mike/OdeToJoy.html

Theodor Frimmel. Beethoven-Handbuch. Breitkopf & Haertel. Wiesbaden: l968.

Owen Jander. Beethoven 's 'Orpheus in Hades': The Andante con moto of the Fourth Piano Concerto. 19th-Century Music VIII/3 (Spring 1985) pp. 195-212.

Adolf Marx. Ludwig van Beethoven: Leben und Schaffen. Georg Olms Verlag. Hildesheim:1979.

Ovid. The Metamorphoses. Translated by David Raeburn. Penguin Books Ltd. 2004.

Reclam 's. Klaviermusikfuehrer Philipp Reclam. Stuttgart: 1968.

Romain Rolland. Essays on Music. Edited by David Ewen. Dover Publications New York: 1959.

Romain Rolland. Beethoven the Creator. Dover Publications. New York: 1964

Mario Roso de Luna. Beethoven Teósofo. Edit. Eyras. Madrid: 1984